West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song is the main temporary exhibition at the British Library at present. The exhibition explores West Africa's relationship with language whether it be oral, written or symbolic. Comprised of 17 nations and with a population of over 340 million people it must have been a difficult decision for the curators deciding what to put in and what to leave out. Luckily they did not leave out textiles.

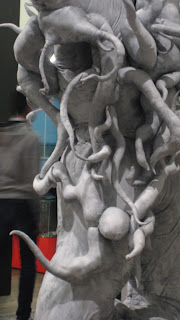

The exhibition begins by looking at some of the region's various societies and how they are bound together with stories and symbols. A major theme throughout the exhibition was how music and song is used to pass down myths and legends, as well as politics and social concerns. Costume and masks often play a major role in the performance of such music. There were masks on display but also films of performance. This did not just relate to traditional West African ceremonies but also the annual Notting Hill Carnival.

There was a section on adinkra and Kente cloth with a display of hand carved stamps cut from gourds that are used to print a variety of symbols that makes this cloth so special. Explanations of a variety of symbols were displayed throughout the exhibition.

One display of printed cloth was that made for the Methodist Church of Ghana's Inaugural Conference (1961) and turned into a dress. It included the name of the conference, topographical images and floral motifs in a bright blue colour - it made a very striking outfit.

At the very end of the exhibition there was a section relating to modern writing - not just as books but as film, radio, even Twitter. Also included was a display of cloth with symbols that alluded to sayings and proverbs. The cloth was given names that reflected its meaning such as "Your eyes can see but your mouth cannot say", "You treat me as if I were a snail" and "Do not put your gold around the neck of a guinea fowl".

There was so much more in this exhibition and I was particularly interested in some of the individual stories that were told in written accounts or even in song. The story of Queen Nanny of the Maroons. She was a remarkable woman with a very peculiar talent.

The exhibition does not shy away from issues surrounding such themes as slavery and colonialism, but the overall impression was of a region full of diversity, colour and joy. There is plenty of music, some to listen to privately on headphones, but also some to enjoy as you walk around the exhibits. I was particularly amused to see a group of teenagers spotted dancing along to the carnival music - not something usually seen in the British Library.

The exhibition continues until 16 February 2016 - see the British Library website for details of opening times and admission prices. The library also has an exhibition about Alice in Wonderland (which I have yet to see) and continues until 17 April 2016. This exhibition is free and in the library entrance hall.

There was a section on adinkra and Kente cloth with a display of hand carved stamps cut from gourds that are used to print a variety of symbols that makes this cloth so special. Explanations of a variety of symbols were displayed throughout the exhibition.

One display of printed cloth was that made for the Methodist Church of Ghana's Inaugural Conference (1961) and turned into a dress. It included the name of the conference, topographical images and floral motifs in a bright blue colour - it made a very striking outfit.

At the very end of the exhibition there was a section relating to modern writing - not just as books but as film, radio, even Twitter. Also included was a display of cloth with symbols that alluded to sayings and proverbs. The cloth was given names that reflected its meaning such as "Your eyes can see but your mouth cannot say", "You treat me as if I were a snail" and "Do not put your gold around the neck of a guinea fowl".

There was so much more in this exhibition and I was particularly interested in some of the individual stories that were told in written accounts or even in song. The story of Queen Nanny of the Maroons. She was a remarkable woman with a very peculiar talent.

The exhibition does not shy away from issues surrounding such themes as slavery and colonialism, but the overall impression was of a region full of diversity, colour and joy. There is plenty of music, some to listen to privately on headphones, but also some to enjoy as you walk around the exhibits. I was particularly amused to see a group of teenagers spotted dancing along to the carnival music - not something usually seen in the British Library.

The exhibition continues until 16 February 2016 - see the British Library website for details of opening times and admission prices. The library also has an exhibition about Alice in Wonderland (which I have yet to see) and continues until 17 April 2016. This exhibition is free and in the library entrance hall.